The Grand Section Guardian #008 - Stop 06, Windorah/MAY 20, 2017

The smallest town, yet some of the biggest thinking. Indigenous elders active teachers, people as usual wearing many hats, playing many roles. The stark white ghost gums seem unique to the place, a beautiful contrast to the blushing red earth.

PLACE

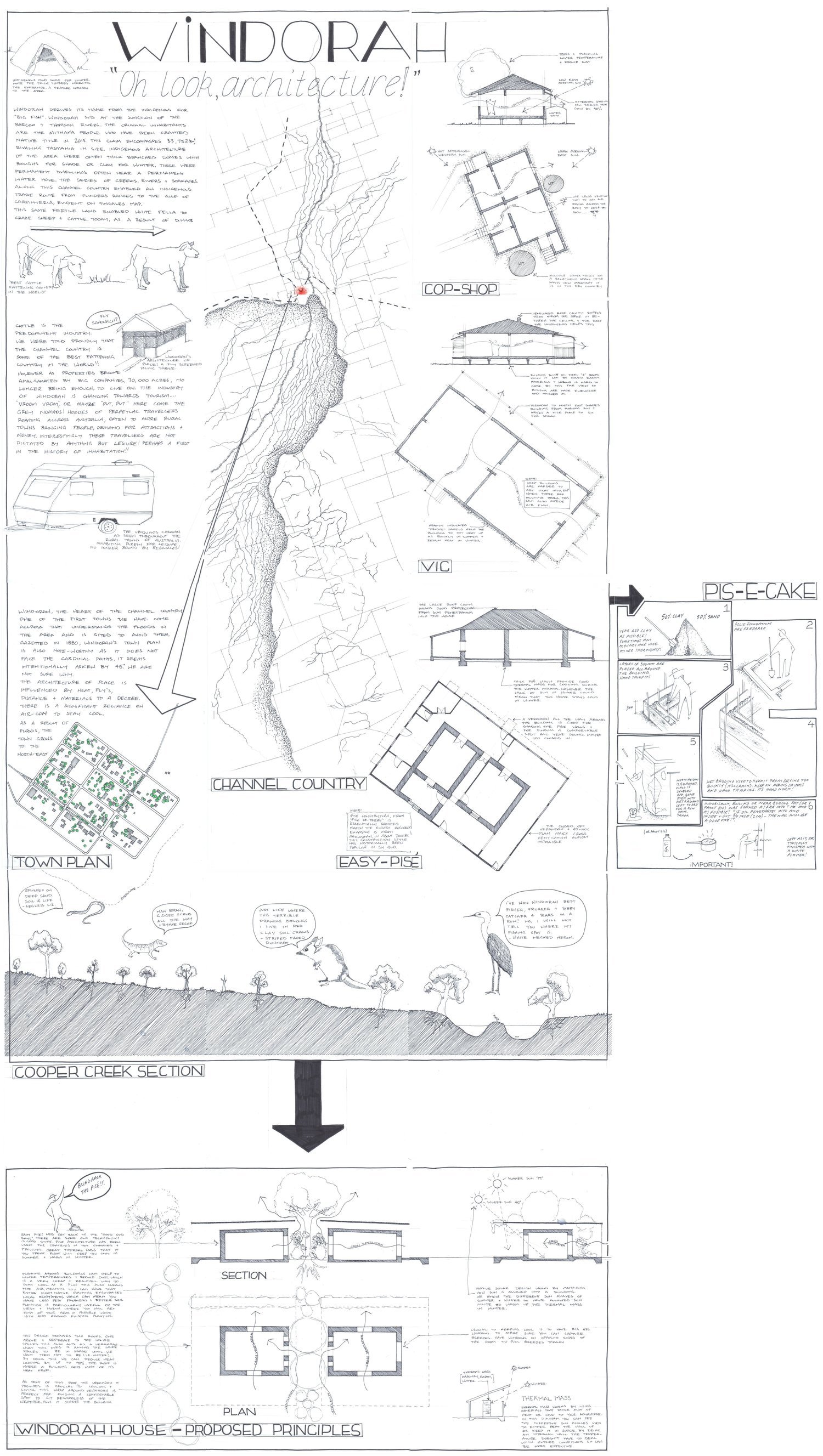

Windorah, aboriginal for “Big Fish”, dubs itself the ‘heart of the channel country’ and is a deceivingly fertile place in water and out. At the junction of the Thomas and Barcoo, two rivers form a creek; Cooper’s Creek, which is the lifeblood of the channel country and part of an ancient link between the Flinders Ranges and The Gulf of Carpentaria.

When in flood Cooper’s Creek can span up to 100kms, acting as a natural irrigation system for vast swathes of country, touted by some as the “best cattle fattening country in the world”. The sweet country is hugely nutritious. To the west, red sand hills, to the east, the black soil channel country.

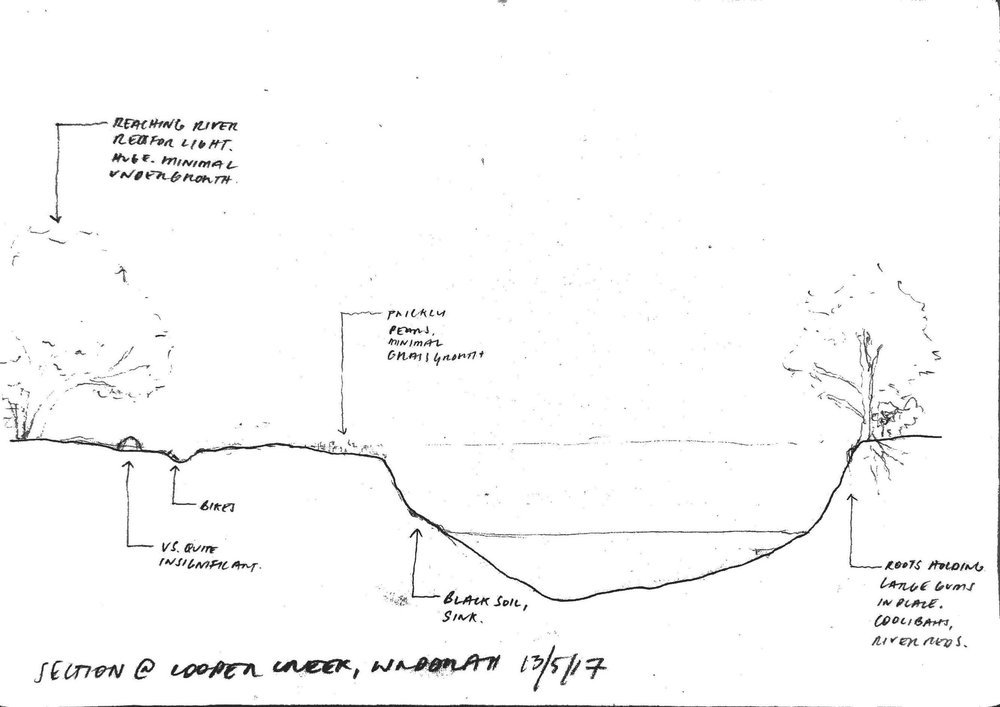

Cooper’s Creek is lined with lignum (a shrub common to inland Australia in areas of high salinity and often by creeks) and Coolibah trees that provides plentiful shade; a welcome refuge for camping and animals alike. White Necked herons hunt for fish and Grey Nomads hunt for yabby’s.

The town of Windorah is situated 10 kilometres uphill west of the main channel. The Coollibah’s and Gums on the river bank edge give way to flat open herb-lands (alluvial plains with a variety of shrubs and grasses growing), where open lignum shrub sits upon deep cracked clay soil awaiting its next flood. Red sand hills rise growing low gidgee in open woodlands and on the sandy hill that the town sits on snugly above the flood line, Eucalyptus, Mulga and Spinnefex thrive.

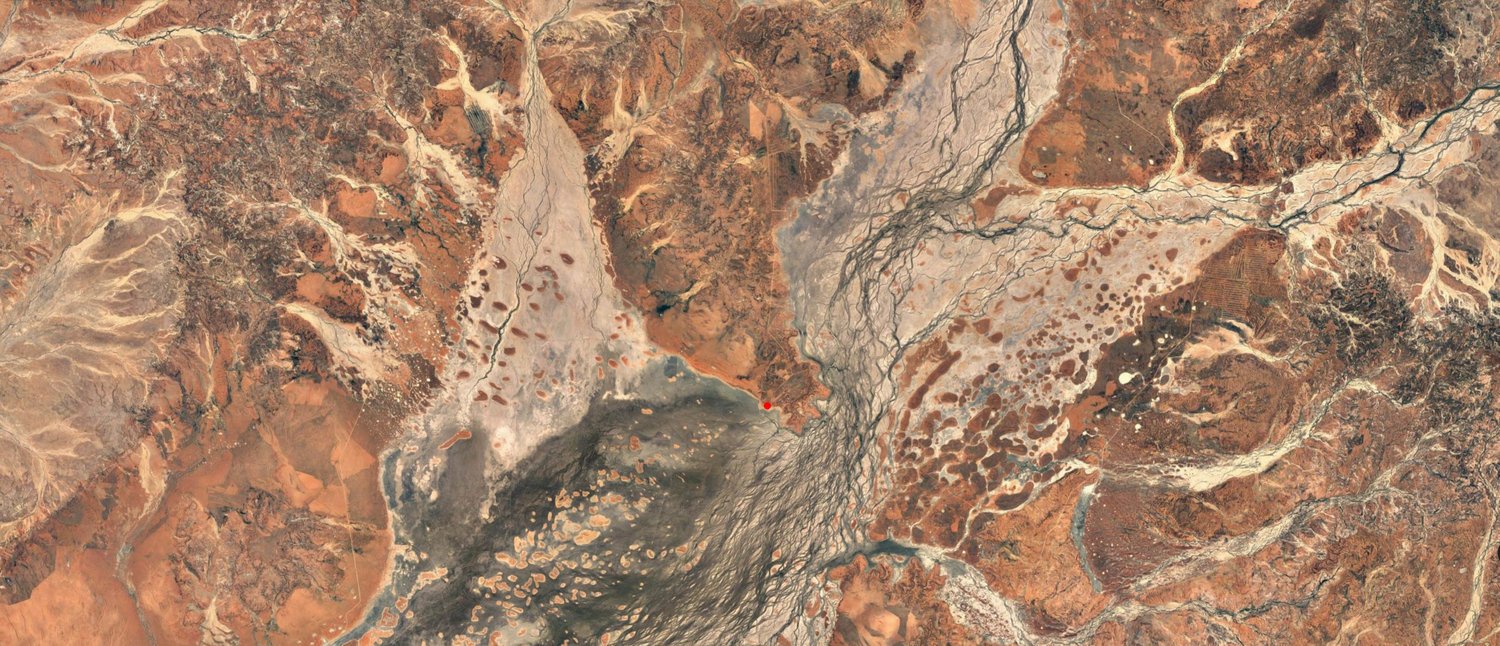

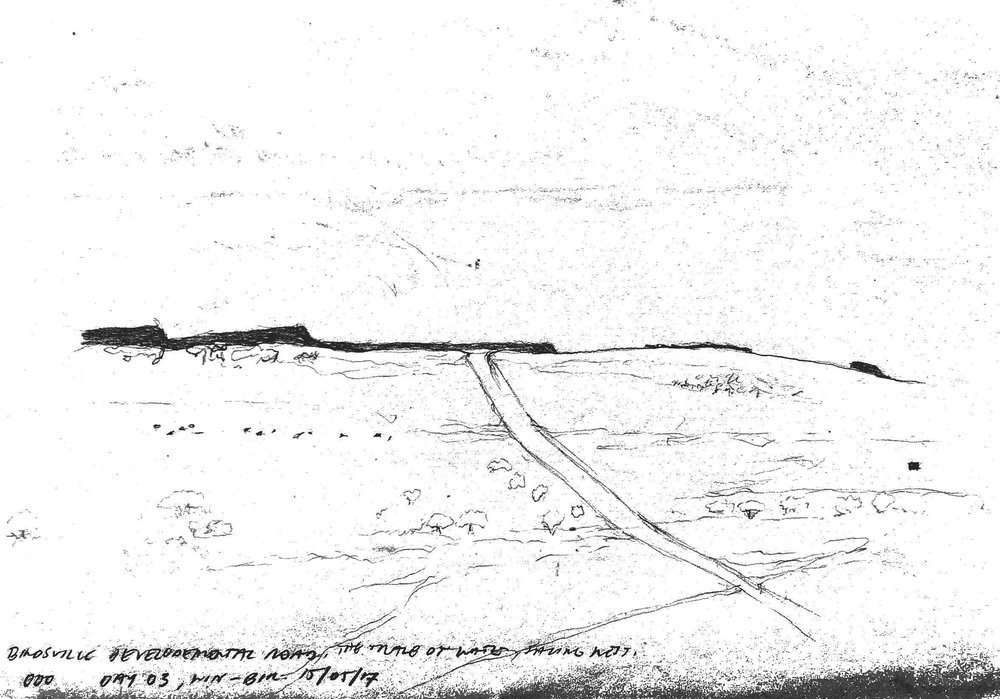

The section from Windorah (left) to the Cooper's Creek showing the variety of vegitation and geological changes all in 10kms!

Unlike all of the other towns we have visited, flooding is welcomed and in fact depended on with the town just sitting out of the flood zone. “There hasn’t been a good flood for five years”, but when the water does come the land flourishes, it is said to be an incredible sight where herbage shoots up quickly over the heights of cars.

Gazetted in 1880, white industries were, sheep and cattle, now moving into oil, gas and tourism as part of the future economy. Road maintenance and a caravan park extension form the backbone of the local work load.

The wonderful channel country as seen from the air, now it all makes sense! Windorah is located safe and sound on a peak in a relatively flood free zone. One of the first examples we have seen of a town being sited with a genuine consideration of place.

People

Told by a helpful local that there was a wildly fluctuating population of 75-80 people we prepared ourselves for anything. Windorah now lies in the Native Title claim of the Mithaka people, whose cultural overseer, George Gorringe took us for a drive to show us some amazing things that he and his people are unearthing. Still very much re-discovering their own heritage through anthropological and archaeological research, George openly taught us lots, we think we are slowly losing our ‘white, city’ eyes. Although talking to an old bushy, Glenn who we met in Mount Perry told us that “you never loose your white fella eyes, they just get dimmer” This country used to be part of an indigenous trade south from Flinders Ranges to the Gulf of Carpentaria.

The local indigenous tribes of the Windorah area were not in fact the Mithaka people according to the Norman Tindale map (below), it was part of the Birria peoples land. As a result of massive displacement to missions as well as a trend of Indigenous mobs clearing out overnight if they suspected they were to be taken from their land (from interview to Indigenous Elder Alice Gorringe from June 2000) the custody of this part of Australia has come under the care of the Mithaka people and their native title determination.

Norman Tindales Map of Indigenous Australian language groups. The highlighted corridor shows a concentration of language groups around the cooper's creek region. It is known there was a significant trade route from the Flinders Ranges to The Gulf of Carpentaria. We have found it interesting this obvious concentration in the vacinity of this historic trade route. (this is guess work)

Upon arrival we were told by the information center that the cops were looking for us, luckily we didn’t have to cut and run, merely a check in. Rob, the local cop, was a constant source of information and support for our stay. Rob and his wife Victoria were incredibly generous to us, paving the way for us by making introductions to the various people of the town to get us in to their houses and minds/knowledge of the place. These connections in a place are invaluable, the locals seem to convince other locals talking that investing time in us is a great idea. It really is fantastic to witness peoples evolving perceptions on ‘architecture’ over our week stay in a place and their learning of principles to employ to improve their living spaces, comfort and impact on place.

Local Police Officer, Rob and his lovely wife Victoria pointing out where we went wrong, Owen is laughing because he hasn't seen it was his spelling yet.

Notably, one lady whose pisé (French term for rammed earth) house we were most interested in at first was skeptical of letting us in and taking time to show us around. The next day we wanted to measure it up and document it to understand how it worked, we had to do no ‘sweet talking’ or anything of the sort. She expressed an air of pretension about us documenting the only pisé building left in the town, because otherwise as she had realized the knowledge would be lost. Just fantastic!

Stuff (Architecture)

At first sight, it looked like the last few towns. Same ideas in ‘Architecture’, move-able buildings, thin walled, air-con reliant structures, shading to the north and west over windows, orientation aligned with the street grid. However as we dug a little deeper we began to discover Windorah’s inherent treasures.

Heat and dust, the two big issues to deal with in buildings. Dust is the easy one, historically the answer was to “open the doors and let it blow through” or close the doors and vacuum later. Now though the use of good seals can assist. The prolific use of grass lawns capture dust and planting around dwellings also reduce dust when present. However we were told dust storms have been less severe lately and nothing like they used to be. Locals believe this is narrowed down to previous overgrazing, historically the place was sheep country. Nowadays sheep have been moved off a lot of the properties and livestock changed over to cattle. Sheep have to ability to overgraze paddocks, biting pasture low, basically at ground level, tracts of land are left bare and take a long time to regenerate.

Heat is slightly more complex, the ubiquitous air-con unit makes its appearance throughout the town, hardly surprising since weeks over 40 degrees in summer are not uncommon. The solar farm at the eastern entry into town looks like it has found the right spot to capture the intense sun, however, talking to locals, electricity is even more expensive as a result, air-con-costly!

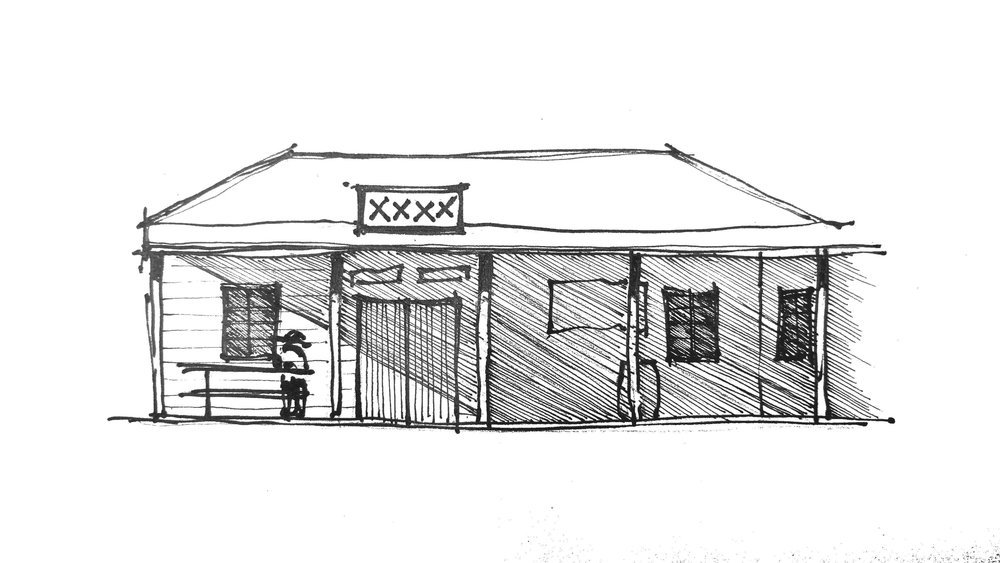

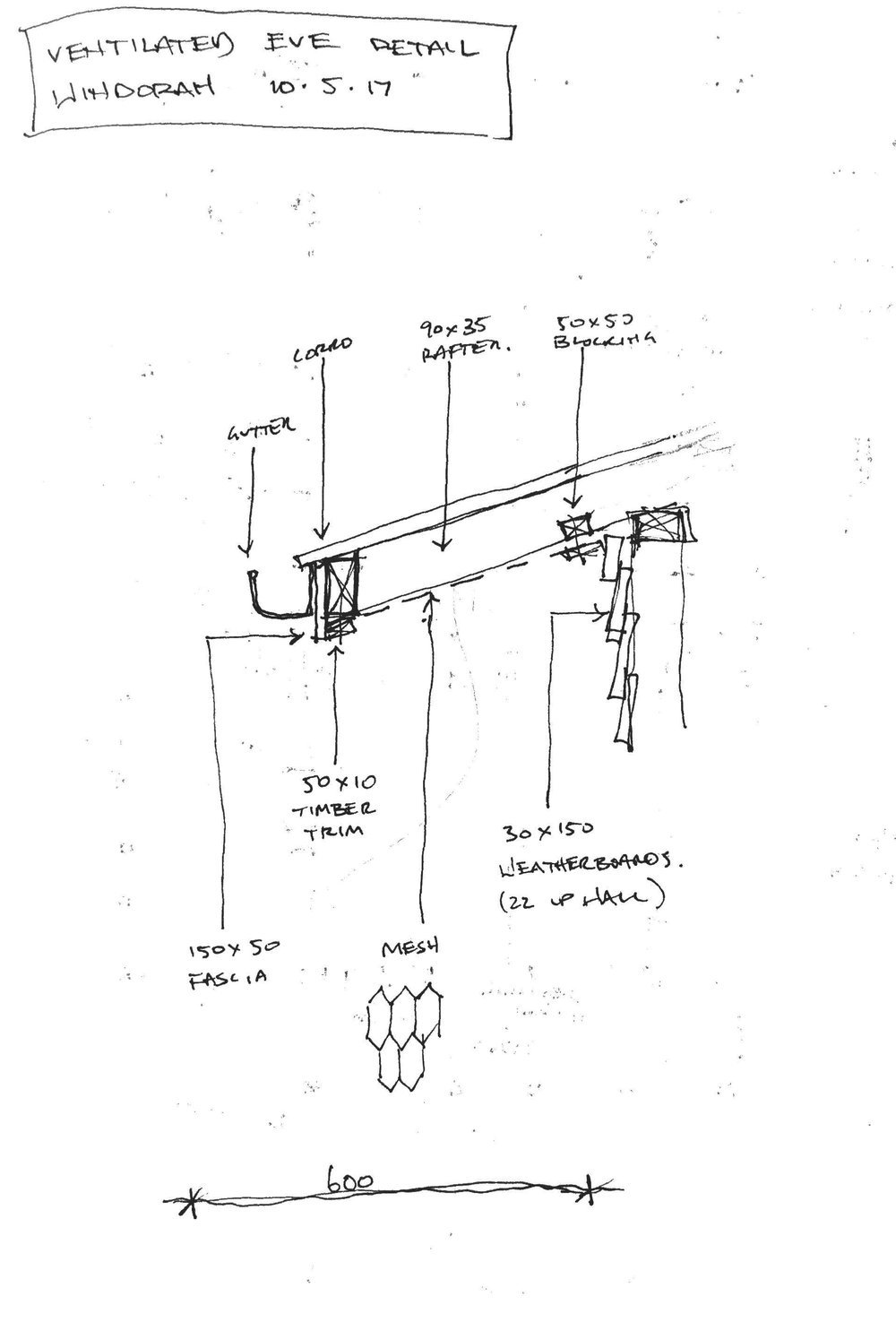

Historically, large ventilated roof cavities, shaded veranda's, a second fly roof along with pisé construction, was a response to this. Now though, these principles seemingly lost. Pisé was once common throughout south-west Queensland, now hard to find is the first one we have come across along Lat 25°. The outback shop’s residence was built in the 1880s and provides a working example of this excellent construction method. Using local materials, such as hard clay from local anthills, and gelatin derived from hooves and horns binds the mixture together to form a solid earth wall where then boiling oil is soaked into the walls to seal them. In the case of the outback shops the walls are a fantastic 500mm thick lending itself to a cool interior.

Easy-Pise (minus the boiled hooves and horns for binding, information we got as feedback from a local cockie). This construction method was once common throughout south-west Queensland. Note Boiling fat used to seal the wall!! Click on this image to link through to a great article documenting early poioneer homes of Australia.

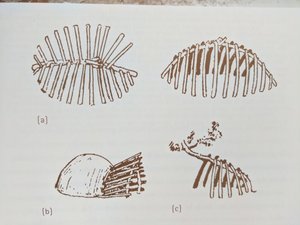

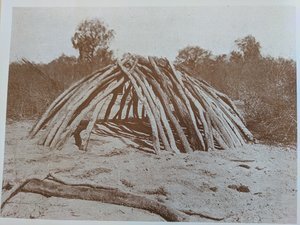

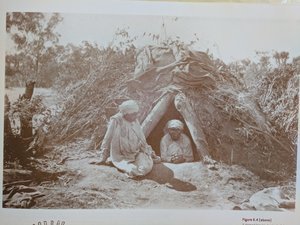

This masonry construction technique draws significant ties to the indigenous buildings that used masonry clad domes for winter use, capitalising on the thermal mass of the clay dome. Traditional Indigenous structures of the areas were often permanent camps built near water holes, using the thick timber from riverside gums to form a dome structure clad in mud that would harden over the structure and then a fire would be lit inside a dug down interior to warm up the clay cladding, being raked out before sleeping. Summer structures were similar dome forms with branches or reed thatching for shade.

Exhibition, FRIDAY 12TH MAY

Our great audience! More interested in our bikes and the ice blocks than architecture the kids loved the idea of building with dirt and realised just how good 'shade' is for different things!

Wanting to work with the local school children, the lack of a blue card prevented it so instead we invited the school along to the exhibition time with zooper doopers (fantastically artificially flavoured ice blocks) as incentive.

What a great experience to have to re-orient ones thought and habit of communication to present to a younger audience. Although the kids didn’t have a clue about ‘architecture’ (who does) we talked about the architectural history of Windorah starting with the Indigenous Architecture and the use of a fire to warm the dried mud, they thought it fantastic stuff. Although mostly interested in our bicycles, if we wear dirty clothes and the size of our tent they loved the idea of building houses with dirt and using shade to cool you down.

Although in a simple format, the locals enjoyed the content, giving great feedback about the buildings we had analysed such as “they also used to boil up cows hooves and horns to reduce them to get the gelatin for binding”. A lot of the information featured was bought to their attention which they didn’t previously realise, where our ‘proposed house’ featuring principles we think suitable for the place was received well. Featuring a “bring back the Pisé!” comment, George thought it a fantastic idea and one that makes sense. The local police officer is keen to experiment and build one!!!

We even took the radical step of proposing building principles that we think could work for the harsh but wonderful Windorah climate. This aims to use the thermal mass of the Pise to regulate internal temperatures, reduce dust and ambient temperatures with planting, massively reduce direct heat loading with the fly roof as well as provide options for outdoor spaces and give the option of 'flushing' the hot air out of the house with generous windows. This proved to be a winner in many ways! Mostly in terms of being able to have a tangible building to have discussions around, with locals dropping in throughout the week constantly informing and changing our direction.

In BETWEEN(in reflection)

Pictures below from our time in Windorah also. From sewing yabby nets with tooth floss to the 'fly-proof huts', evening drawing and general stuff.

We met some bikers (motor) at the Windorah servo and asked what the road was like west, to Birdsville. “Pretty boring” came the reply, though we know that is the perception of most. WOW, were we in for a shock! Perpetually changing landscape, vegetation, geology and topography kept us on our toes and made riding a pure delight. In fact, we couldn’t ride slow enough even though we were on a washboard gravel road, except for 30kms west of Birdsville, that headwind can get stuffed.

Grasses changing in a definite line at the base of sand hills demarcate changes in soil, moisture and flood lines, these seeming to be the most fertile covered in trees and shrubbery. Clay pans devoid of vegetation termed as “waste land” scatter the tussock-ed plains, changing into rock (gibber) fields of a red sheen that stretches between sand hills. The soil changes from fine blushing red sand to brown, white and yellow dirt. The cattle are plump and healthy, though looking one wonders how it is so. The dry sweet feed is the answer.

Talking to a long associated local cockie (farmer) out of Birdsville we inquired about native title considering our great experience with George in Windorah. We asked if it had any effect on his property or farming and were met with the response; “No, cause they know if they came on my property I would shoot them”. Upon questioning further, bringing up acclaimed texts such as Bill Gammage’s work and their content on indigenous farming and land management as justification we were met with a baffling display of an apparent unwillingness to consider other ideas.

Using these texts to inform our ‘white, city’ eyes we believe there can be no denying that the Indigenous people of Australia made vast and sweeping changes to their environment. Their inception onto the country saw the mega-fauna become extinct as a result of hunting or changing environments (Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens). Even white explorers journals document the extensive agriculture and land management and commend the soil conditions and “park-like” appearance of countryside that grew abundant yams, grains and native fruits (Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth). Active aquaculture saw coastal and inland stone fish traps and managed animal catching traps and thinking (Bruce Pascoe, Dark Emu). The architecture of the Indigenous Australians still has so much to teach us about our own country and how to design for it (Paul Memmot, Gunyah, Goondie & Wurley), the architectural history of a place, for us, begins there.

Cheers,

(getting really) Dusty & Thirsty

Edited by the wonderful Jen Richards