The Grand Section Guardian #014 - Stop 014 Uluru/september 15, 2017

LANGUAGE WARNING:

THERE IS A LOT!!

THIS IS A BIT OF A BEAST OF A BLOG BUT COVERS GROUND THAT IS AT THE CENTRE OF AUSTRALIAS BLACK, WHITE RELATIONS AND HAS BEEN FOR OVER 100 YEARS!

--------------------------------------------------------

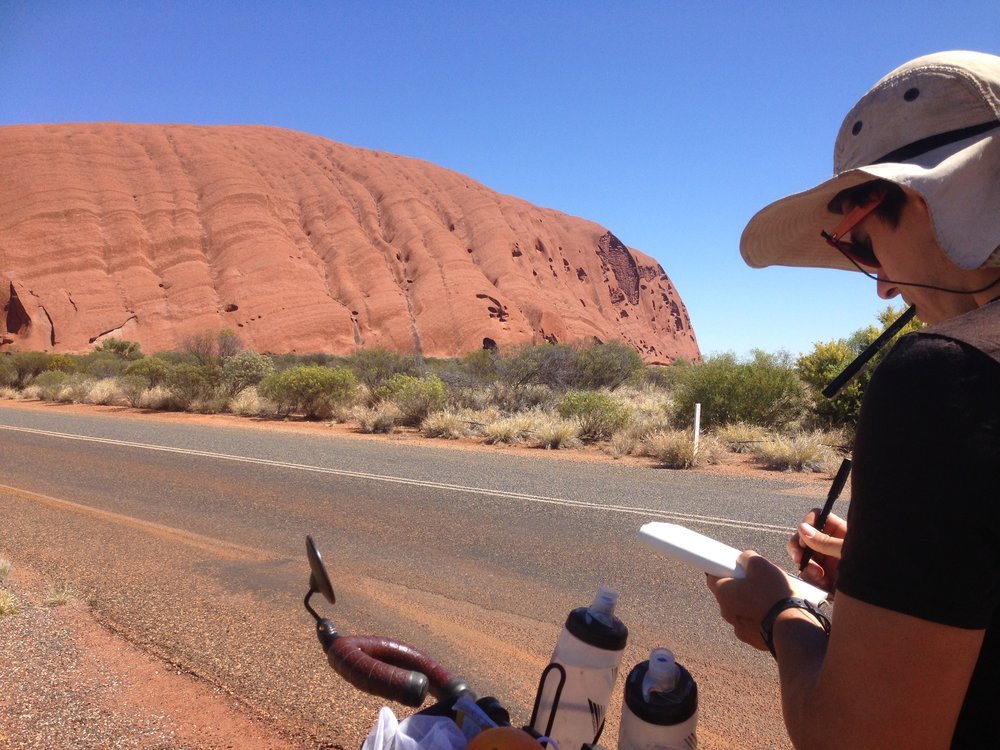

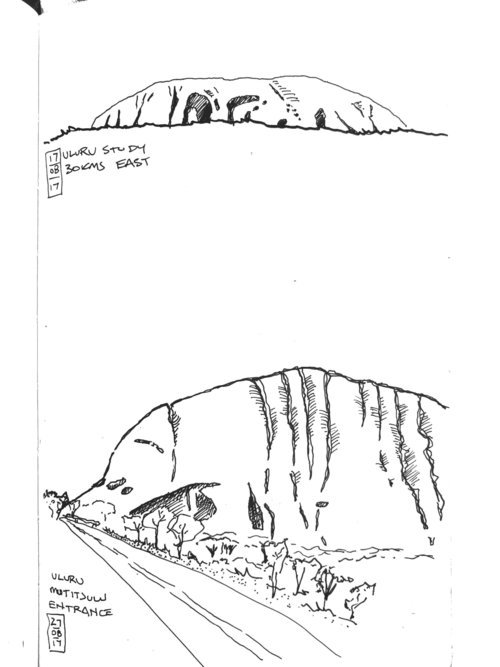

Well shit, the arbiter of the whole Grand Section, the heart of the nation, the spiritual center, the symbol of Aus-bloody-straya,…we made it! This epic place is inhabited mostly in the “township” of Yulara (Ayers Rock Resort), a 1983 purpose built town as a comfortable base for viewing Ayers Rock (Uluru) and The Olga’s (Kata Tjuta) as they were known. Uluru’s massive scale, isolation and abruptness does make this place truly powerful. Light changes on the faces of the rock constantly, revealing hidden cracks, colours and forms day by day. “No day is the same” the rangers tell us and we begin to understand.

PLACE

17th - 26th August 2017

According to the Anangu people this incredible landscape was created at the beginning of time by ancestral beings with Tjukurpa (the law) governing all.

For us white fellas, an Arkose sandstone[i] geological burp erupted from the Alice Springs orogeny[ii] about 400 million years ago tilting a section of the 500 million year old sea bed 90 degrees forcing it up to a whopping 348m high (that’s higher than the Eiffel tower). This buck-wild geographical fiesta has left a cultural nugget that whilst on the surface is impressive, extends 5-6 kilometers underground as well (possibly).

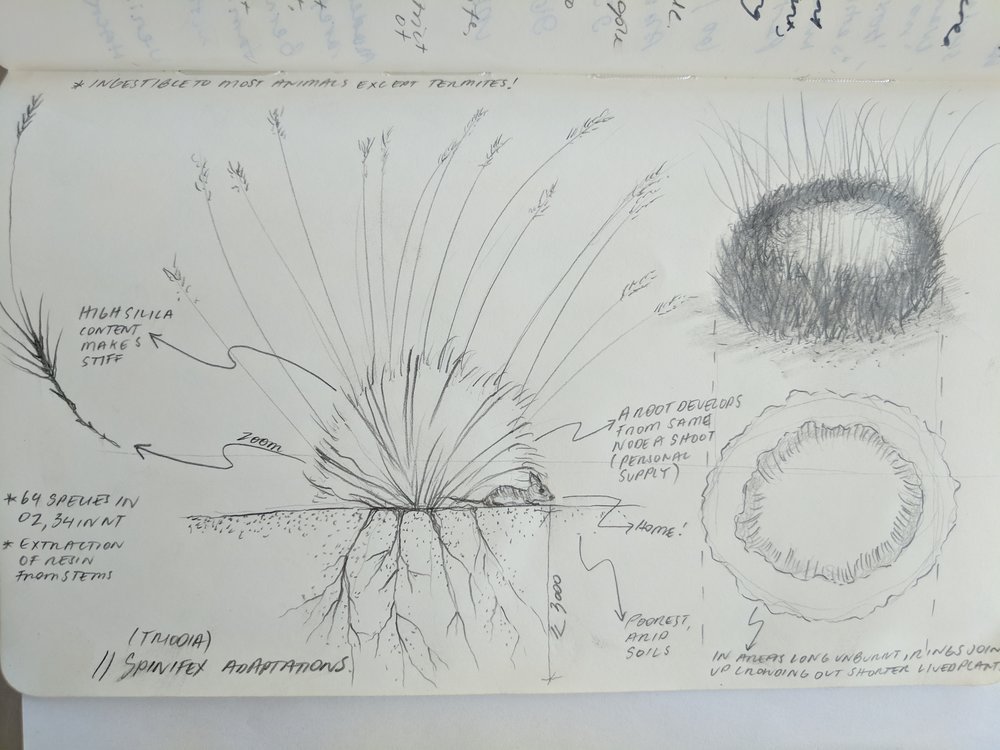

Today this is largely referred to as Uluru, the official and Aboriginal name. Similarly, Kata Tjuta (The Olgas) was pushed up by the same orogeny but not by so many degrees. Both of these radical geological party poppers are a result of the once Himalayan sized Petermann ranges, eroded remnants that over millions of years and underwater pressure formed Uluru and Kata Tjuta. Apart from these two impressive rock formations the surrounding landscape today is undulating red sand hills covered in Mulga, Spinifex and Desert Oak scrub. This contrast amplifies the power of the massive rocks that dominate the landscape for a 50km radius.

Uluru has been a powerful and sacred place for thousands of years. Inscribed into the shapes of the rock are Indigenous stories, lessons and embedded history. Sacred sites for both men and women comprise the rock. It wasn’t until the 1950’s that tourism began its steady and tightening grip.

The closest ‘town’ is 463 km away, namely Alice Springs. Emergency services for people stuck on the rock climb still fly from Alice Springs, which can mean an overnight stop for people before being air lifted to safety and as a recent story goes, a $78,000 bill.

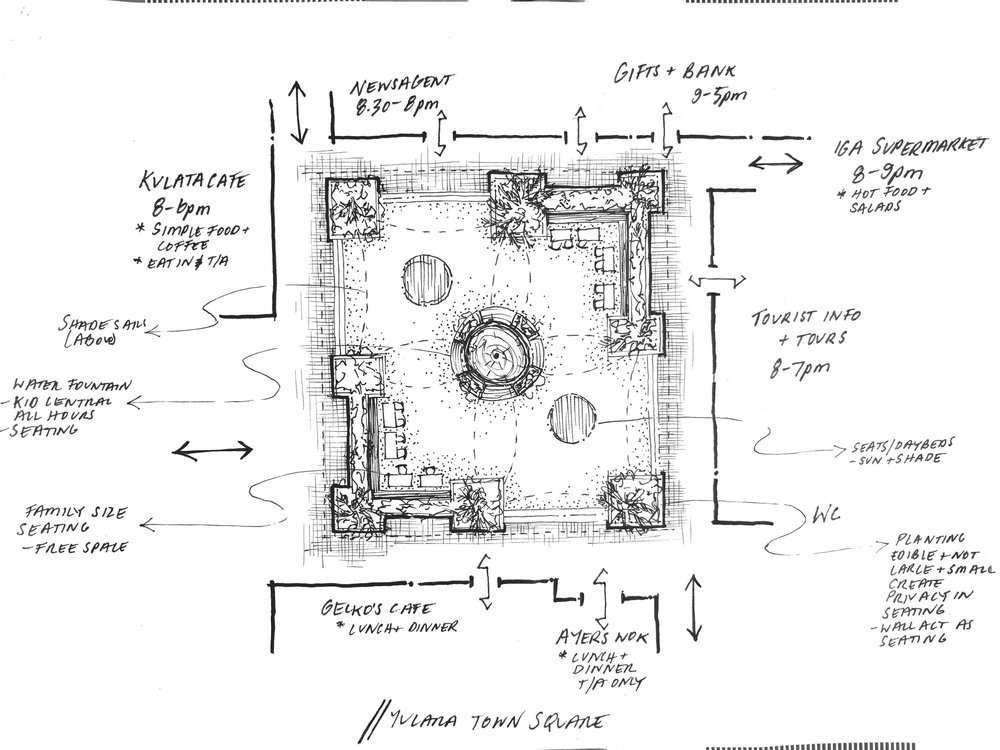

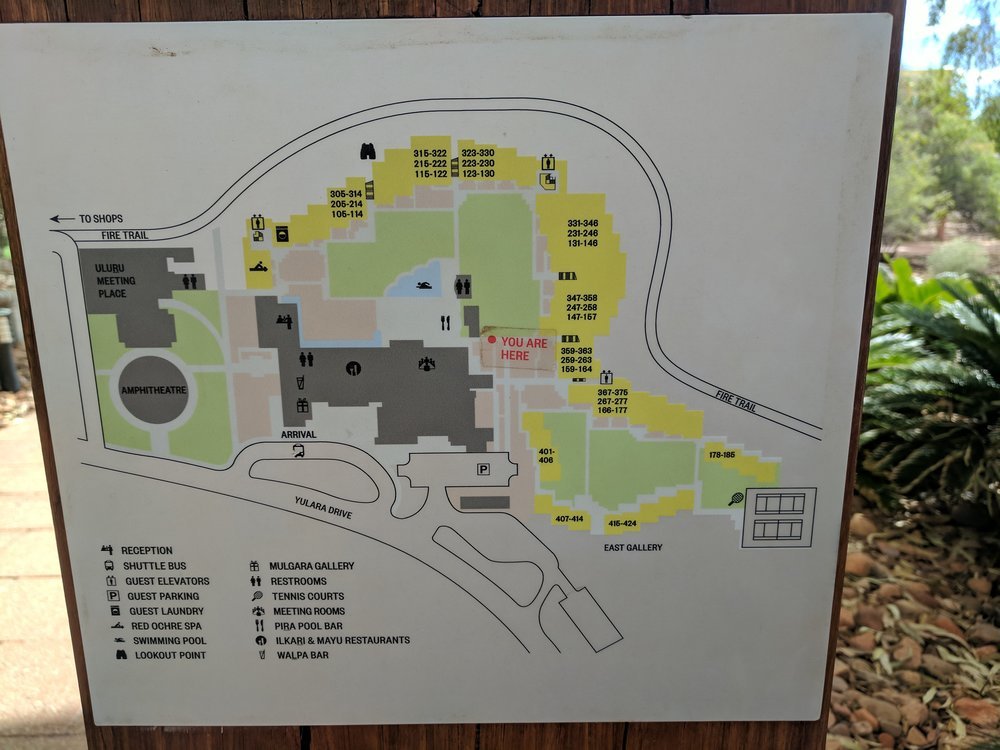

Only 21km to the North West of the rock itself is the township of Yulara, the fifth biggest city in the territory (so we’re told) causing Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park to be the biggest contributor to the NT economy. So whilst it is incredibly isolated, there are 14 places to eat and drink, a police and fire station, wifi, three art galleries, supermarket, post office, conference center and souvenir shops not to mention the 65 tours and experiences that are on offer from the hotels and tour companies. With a transient staff population of 1200 and upwards of 400,000 people visiting the national park every year this place has huge infrastructure to cater for the demands of tourism.

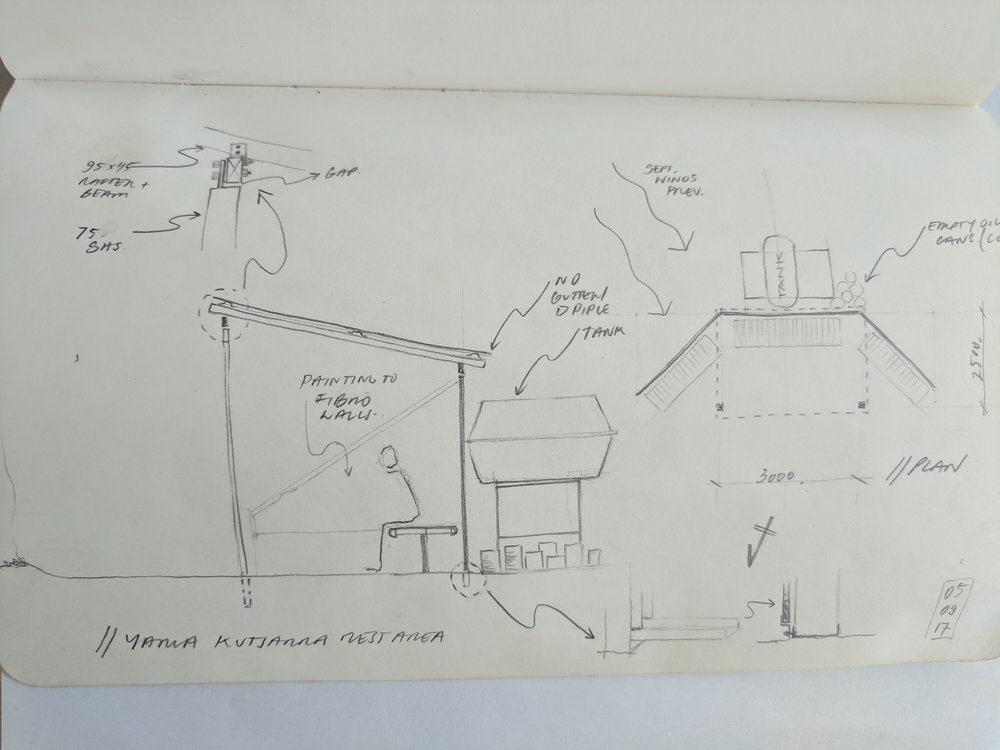

Sitting quietly to the east of the rock is the closed Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu, a town of about 300 people with “Rangerville” (surprisingly, ranger accommodation) existing as a semi-detached extension of the same infrastructure. Mutitjulu began an outstation in the early 1970’s however the use of this land and connection to place goes back millennia.

Regardless of this, the township itself has already had a complex and pivotal history.

People

People exist in three distinct places in and around the Uluru area, these are, Mutitjulu, Yulara and “Rangerville”.

MutitjuluThe true locals at Uluru are the Anangu; Yankunytjatjara, Pitjantjatjara and Luritja people who speak their own languages, largely living in Mutitjulu and jointly managing with Parks Australia the Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park. The township of Mutitjulu, a kilometer or so from Uluru in the National Park itself is a community full of depth, connection to place and a history of survival. Access to this place is restricted to only those invited, family or with permission. An oversaturation of white-do-gooders (many with noble intentions) appears to have led to an aversion to walk-ins. This has the effect of segregating the aboriginal and white/tourist mobs from one another as well as the ability to engage at anything more than a tokenistic level.

The Anangu people first met white fellas when the explorers Ernest Giles and William Gosse crossed the region in the 1870’s. The 1920’s saw the creation of the Petermann Aboriginal Reserve (including Uluru) intended as a refuge for Aboriginal people from contact with European society, pastoralism impacts on water and the landscape and other pressures which were contributing to people moving away from traditional country. Since the 1940’s the focus from government has been conservation and tourism. From 1936, tourists started to come to Uluru, and as interest increased ad hoc accommodation facilities were built at the base of Uluru with aboriginal people being actively discouraged from visiting or staying. 1958 saw the area including Uluru and Kata Tjuta excised from the Aboriginal Reserve and gazette as Ayers Rock-Mount Olga National Park (named by Giles and Gosse). Aboriginal people had no rights to enter the area. As a result of the 1976 Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act, a 1978 submitted claim along with great lobbying and an Act amendment saw in 1985 a large ceremonial ‘Handback’ event returning the National park to its traditional owners.

“This is an historic decision and is a measure of the willingness of the Government, on behalf of the Australian people, to recognize that just and legitimate claims of a people who have been dispossessed of their land but who have never lost their spiritual attachment to that land.” – PM Bob Hawke, Launceston Examiner, 12/11/83

HOWEVER, there were imposed conditions including the 99 year lease[iii] of the land back to the Commonwealth government as a national park managed by Parks Australia with a portion of receipts going back to the Traditional Owners. And so, that brings us to today with 67 years remaining. Tjukurpa (Spiritual Law) continues to determine the responsibilities of the present-day Anangu and their relationship to country created by their ancestors.

Moreover, Mutitjulu was ground zero for the Intervention back in 2007. The government sent in Police, ADF troops in tanks and convoys uninvited of course to mark the beginning of the policy reforms.

“…a lot of our mothers who’d experienced the Stolen Generation. They ran up to the sand dunes to hide their kids, so you can just imagine they were reliving something they’d experienced”[iv].

Whilst we were there Men’s Business was on, yes they still practice ceremony here! A cultural space that restricts access for anyone else in certain parts of the community and or landscape to allow them to carry out their sacred business which after they then travel thousands of km’s down to SA picking up elders and other men along the way. Female Anangu rangers and Mutitjulu residents have to be back into the town by 2.30pm inside their houses, leaving work and other duties to avoid any contact with the business which is forbidden. Ideas that our Western employment and cultural frameworks would struggle to accommodate.

Gary Cole

A community leader at Mutitjulu we were lucky enough to catch up with, in between him juggling lunch, his 6 month old son in arms and managing the local council workers. Gary talked passionately about how Uluru was his peoples place. He acknowledged that Mutitjulu has many issues similar to other indigenous communities; low local employment, poor housing stock and overcrowding. Observing that the intervention was a massive shock to the community with accusations thrown at many of the towns men (where 10 years on still nothing is proven), injuring pride and community cohesiveness.

Gary was optimistic and aspirational about the future of Mutitjulu whilst skeptical and not particularly empathetic with Yulara and the management there. There are community plans to create a campground for tourism, lifting the no alcohol ban and building a club house for sports and social events so the locals have a place they can hang out. Due to the township bans residents are prohibited from purchasing alcohol in Yulara or having a drink at any bar. Interestingly Gary talked a lot about the prospect of 2084 when the 99 year lease over the National Park is over and the control of the Park is handed back to the Anangu people. Once this happens Mutitjulu has the touristic honeypot that is their cultural heritage by the balls.

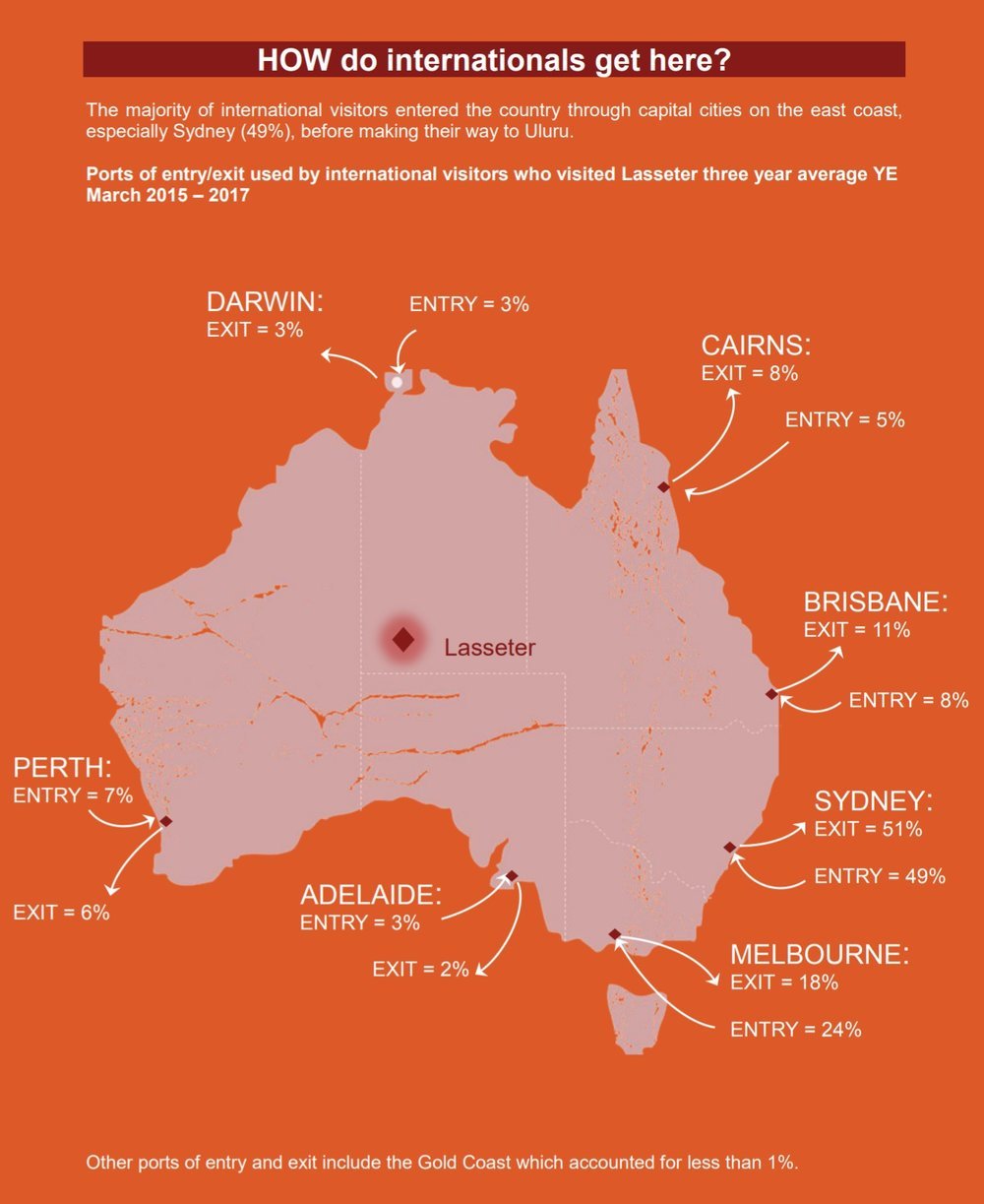

YularaThe big beasty on this bit of track is Yulara (Ayers Rock Resort), the purpose built tourism township of Uluru. It is noted as one of the largest resorts in the Southern Hemisphere comprising usual ‘town-like’ facilities as mentioned before.. blah blah blah. With a staff population of about 1200, most of these transient mix-bags stay for an average of 13 months which has increased in recent years. Some of the “long term” residents are reaching the 9 year mark, however these are few and far between. Workers are often there to work for their stint, save cash and then head back to the coast to their previous lives. Yulara is managed by Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia, owned by the Indigenous Land Corporation (ILC) where from 2011 the ILC established an Indigenous Training and Employment Strategy with a 2018 goal of 50% Indigenous employment. They proudly boast that at the end of 2016 they employed 318 indigenous staff (37% indigenous employment), of which is only 6% local Anangu[v] (which equals 19.08 people). There was a heavy dose of skepticism towards this statistic by the Local Rangers agreeing the lack of local Anangu comprising workforces.

Kulata cafe is the go to place in Yulara town square for a $9.50 pie and salad and is where Voyages "National Indigenous Training Academy" operates as hospitality training. In the smallest font on the page you will notice that this is also funded partly by the Australian Government.

Peter White (General Manager of 1 of 4 hotels)

The General Manager of one of the 4 hotels was massively generous in shouting us a drink and giving us his time by meeting up at very short notice to talk about Yulara, Voyages (managing company) and the future of the place and tourism. Peter is in charge of 282 rooms and self-contained apartments which at the time we talked to him were almost all full, hardly surprising when 90% of people who visit Uluru stay at Yulara. He has been there three and a half years and is really enjoying working with young staff in the Indigenous training program finding it much more rewarding than similar hospitality positions. At almost bursting levels of occupancy Peter mentioned that they need more rooms to accommodate the growing demand of tourism. Apparently in the late 90’s Yulara laundry was the biggest in the southern hemisphere. Peter says the Voyages team has been working with the Mutitjulu community since 2011 to build better relationships but thought that since they are a closed community they wouldn’t want to build any tourist facilities. Interestingly Peter made the point that their high Indigenous employment is a tourist draw card with older Australians appreciative of the everyday interactions they can have with Indigenous Australians at Yulara regardless of where their mob are from.

Rangerville

The intermediary of these two worlds is “Rangerville”, the semi-detached arm of Mututjulu where the National Park Rangers live and walk their adopted and wormed camp dogs[vi]. Consisting of fenced houses that rotate owners as people move jobs or positions this ‘suburb’ has a comfortable yet persisting temporary feel. Juxtaposed with the permanence of the Mutitjulu community proper, the houses are disguised around dunes comprising same design and materials as the community houses. The semi-hap-hazard feel of this place contrasts with the touristy cleanness of the township of Yulara.

Tegan Sharwood (National Parks)

Team Leader of Visitor and Tourism Services for the National Parks, Tegan is actually Owens old school friend who was kind enough to have us stay and pick her brains. An experience that we cannot be more grateful for, it is only through this interaction that we were able to see multiple sides to the Uluru inhabitation. Tegan was not only a generous host but an inspiring woman, and oh my, what a woman!! Her incredibly varied work was tiring to try and even get your head around and keep up with. She is in charge of a lot of things including a constantly changing team of what should be a minimum of eight people whose duty it is to ensure all media teams (eg. Nat Geo filming), photos and communications are authorized, briefed and monitored. On top of this (mostly due to staff shortages) she also has to man toll booths, clear the park, go on cultural trips on country, give guided ranger walks and be pleasant to tourists who recognize her from their daily activities and most annoyingly in the supermarket line. Tegan is well aware of her transient role as a white fella working largely with indigenous people and often marveled at the optimism and resilience of the traditional owners of the land. She speaks bits and pieces of Pitanjarra (and is still actively learning) as a way to strengthen her daily navigating through huge cultural, language, environmental and management spaces she is challenged with. Remote living in and around Indigenous communities and a predominantly male scene, although challenging is clearly formative and educating when you chat to Tegan with our favorite line remaining, “yeah.. out here you’ve got to grow a pair”.

The wonderful Tegan, her adopted camp dog Bear, Bobbie "Bloody" Bayley and the two mighty steads in Rangerville.

Stuff (Architecture)

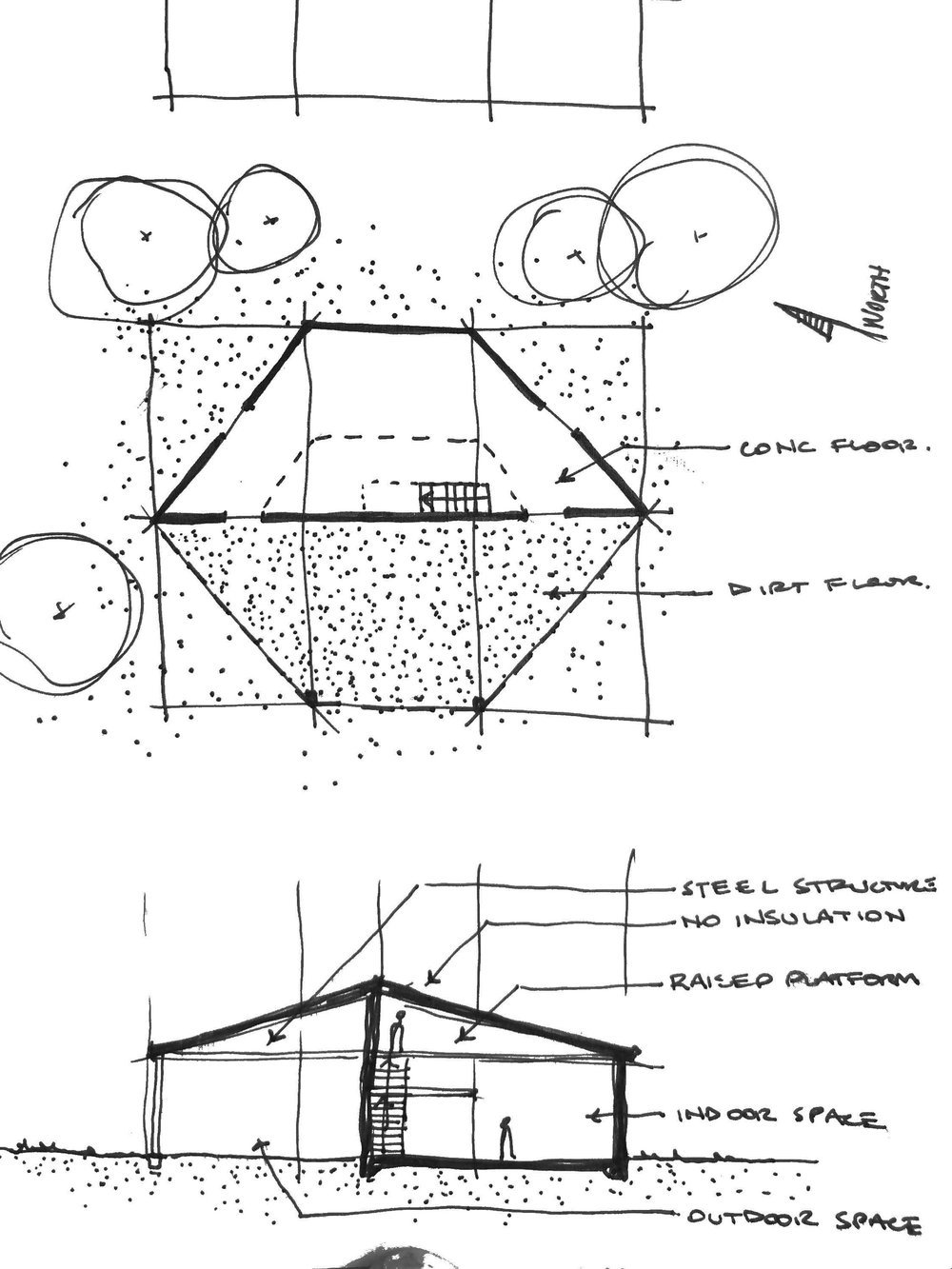

Part of a history of the Western Desert region, the true local architecture often consisted of Spinifex clad lightweight structures. A high level of movement characterised these tracks of land and so anything more substantial would be a waste of resources. It has been noted that the calloused soles of the feet were used to harvest the spiky spiifex for cladding. Some reports indicate that this cladding could be up to a metre thick. This cladding has been re-adapted by the structures around Uluru and can still be seen at the Cultural Centre and Wiltcha's (shades) that dot the Uluru base walk. However, the maintenance of this is starting to become problematic as skilled spinifex tradesmen are few and far between.

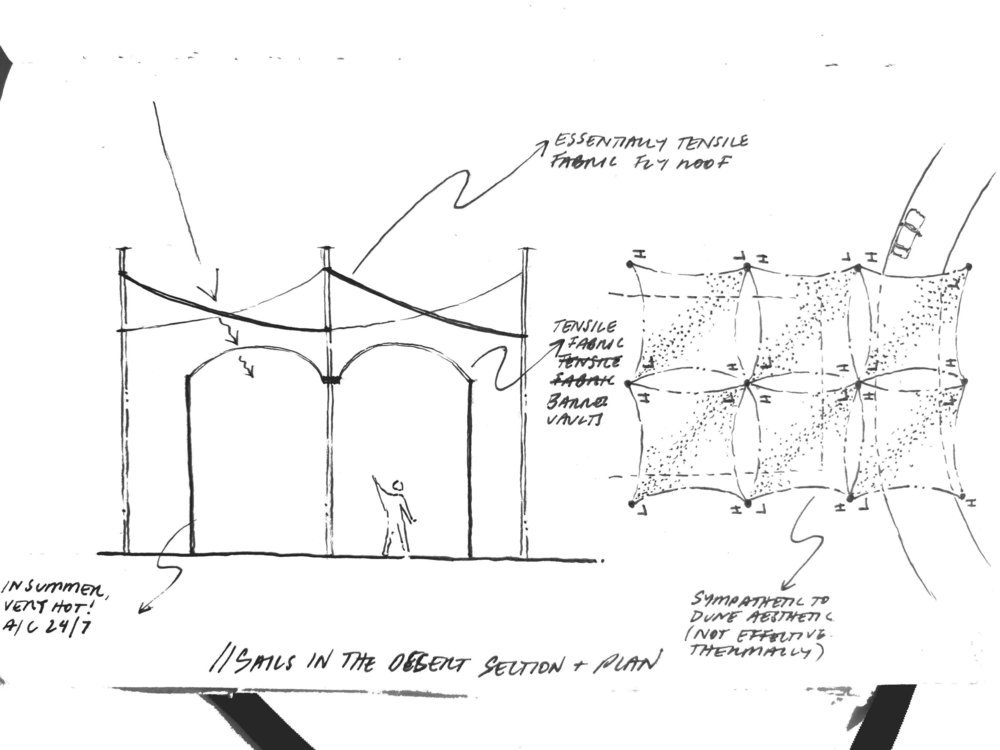

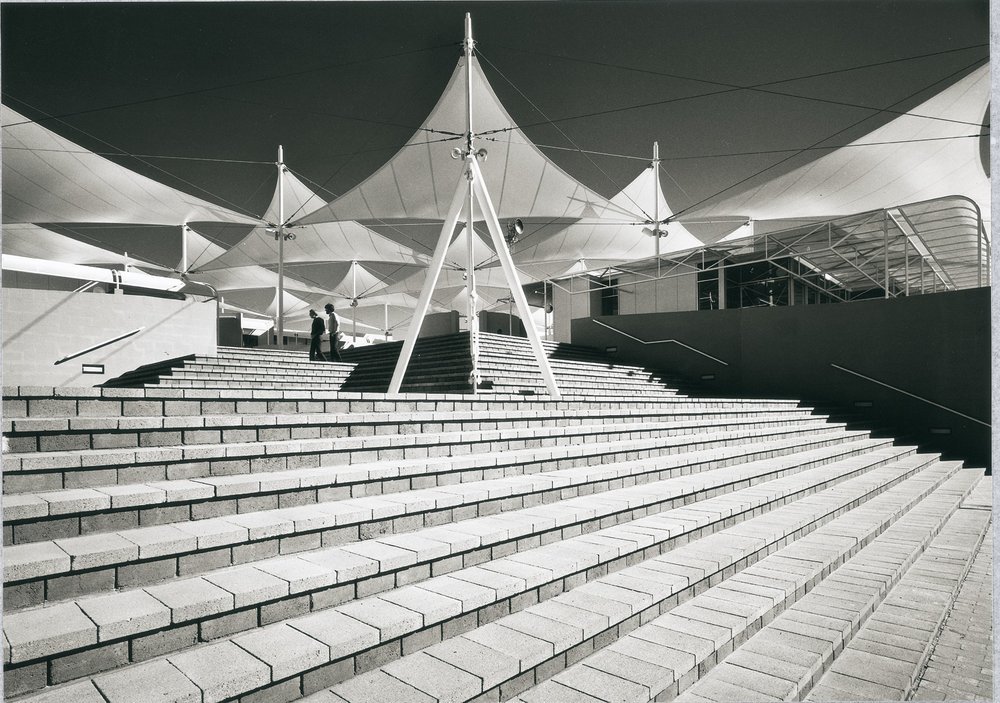

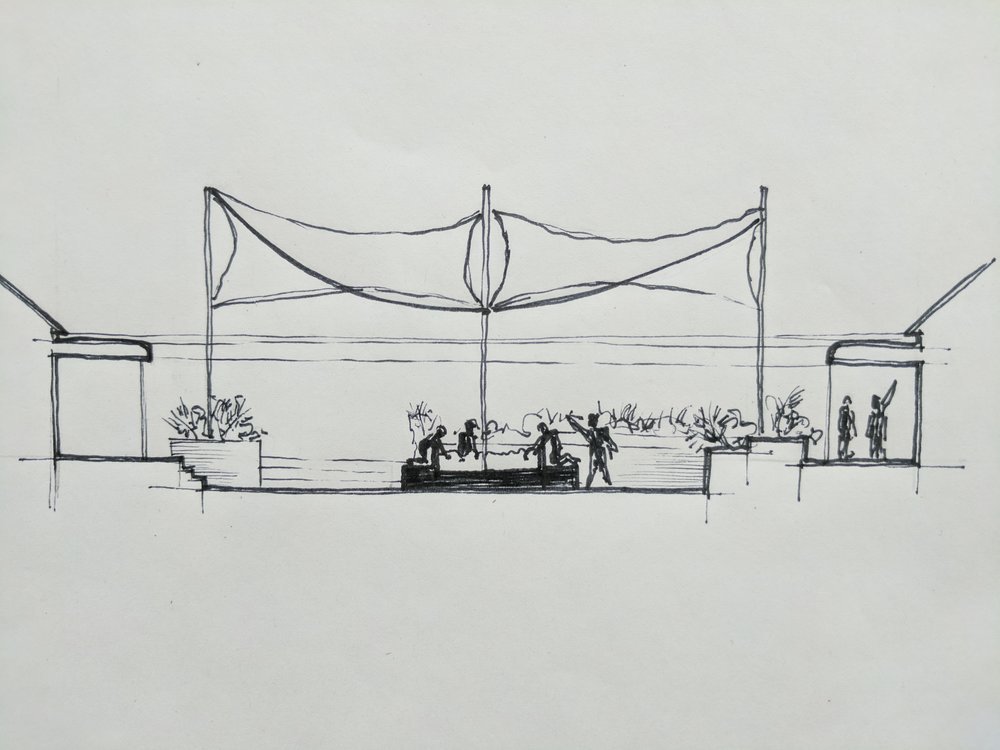

Tourism started officially in 1950 with a base camp to the west of Uluru, by 1958 there were 2,296 official tourists who undertook the 12 hour journey from Alice Springs to see Uluru. An explosion of road works led to an explosion of tourist so that by 1968 there were more than 23,000 people a year visiting the rock[vii]. This huge increase in visitors led to a decision in the 1970’s (By some chump) to move the tourist centre away from the rock to its current location. The Yulara township (Ayers Rock Resort) was a two hotel proposition designed in the early 1980’s by Phillip Cox Architects, a 200 hectare, $120,000,000 development, sensitively located in the swale of the dunes which mask views of the rock from the resort (and each other) kitted out with solar panels and tensile fabric roofs to reduce heat and sympathize with the landscape. Extensive native planting and gardens along pedestrian walkways are used in an attempt to reduce the environmental impact of tourism[viii]. The expansion that has followed over the years to what it is now catering for upwards of 400,000 people a year. Think of it as Canberra moving half way across a continent every year!!

The solar system (haha solar system, not stars and shit sorry) installed in 1984 has become obsolete as the innovative technology used didn’t stand the test of time of the harsh desert climate. Today there is a shiny new 1.8MW photovoltaic solar power system (essentially turning light into electricity with semi-conductors), expected to offset a minimum of 2733 t CO2 per year and which according to the hotel brochure can produce 15% of the Resorts energy needs and up to 30% when real sunny! We’re talking hot hot hot! Interestingly though, this is the maximum solar power the resort will use as the energy companies will not allow them to produce more, a story we have heard more than once. Onya energy companies!! Energy is otherwise fueled by compressed natural gas bottled up in Alice Springs and trucked out to fuel the power station in the vicinity of Yulara.

The Solar Feild in view of the road as consious decision to make a statement by Voyages management.

To cater for the self-dubbed “oasis in the middle of the desert”, three 55 meter semi-trailers make the 1663 kilometer bi-weekly trip bringing supplies and luxuries to the oasis from Adelaide. In 2015/2016 these trucks were back-loaded with 2649 tonnes of glass, cardboard, steel and paper to be recycled in Adelaide. The remaining 6,058.5m3 of rubbish is buried at the resorts own tip and burnt, like most rubbish tips today (surely in the 21st century we have a less archaic way of dealing with waste?). Water from 17 bores is pumped up from the 7000 year old water reserves inside the Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park to water people, fountains, pools, washing machines, toilets, café’s, taps and gardening. The shallowest tapping into the reservoir at a mere 29m, with the ones in use being rotated regularly.

The award winning Cultural Centre designed by Gregory Burgess in 1993 has a strong place in the minds of the Mutitjulu locals yet has differing opinions from the maintenance manager and rangers. Mutitjulu residents were a part of the consultation process, employed as tradesmen and labourers, used local materials and hand made the mud bricks and laid them. There is still a sense of ownership and pride over the space. Other great principles such as radially sawn timber to minimize waste were employed. The mud brick is seen as a tedious material by management, hard to maintain where timber is worn and failing due to the harsh environment. Copper roof tiles are obscenely out of the budget to repair and replace.

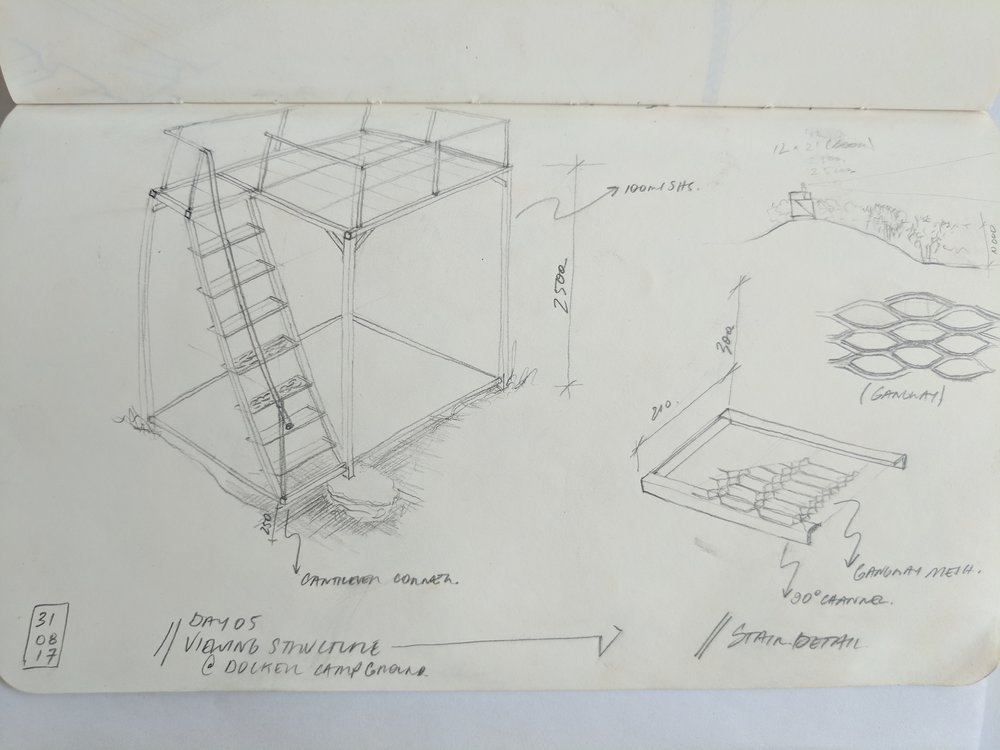

Similar circumstances exist with only 9 year old constructions as well, the Talinguru Nyakunytjaku sunrise viewing platform is a highly considered design of steel and timber, quite beautiful. Steel seems to be the best performer, we were told “if you can keep it away from electrolysis its fine. You have to somehow earth the steel and you’ll have no rust”. Timber is used for its ‘aesthetic’ yet it just doesn’t last. Requiring regular maintenance (when maintenance lists are endless), if sand blows and builds up leaving it in any way in contact with the ground it’s end is nigh, termites move in fast and feast away.

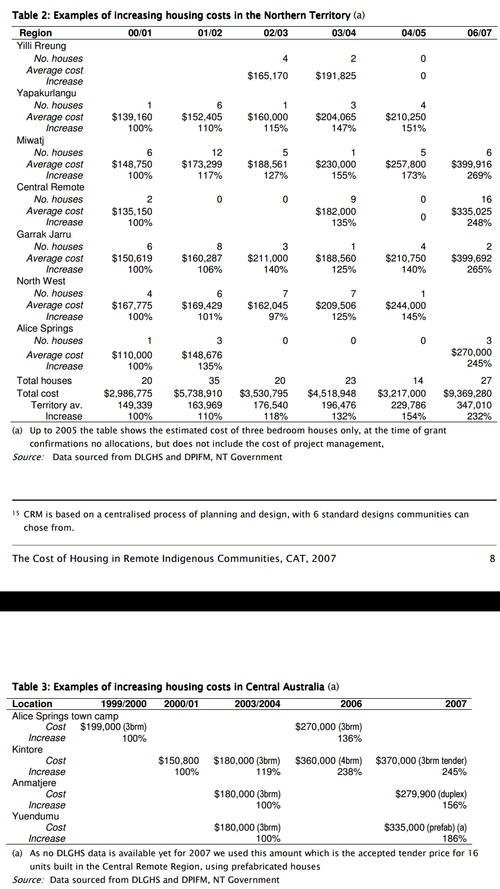

Housing in Mutitjulu is a similar story as the other Indigenous communities we’ve been through. A lack of consultation, poor construction and maintenance and culturally insensitive house design means that houses just don’t work as they should. A typical 3 bedroom home can have up to 20 people at times staying where the older generation still prefer to sleep outside and be around fires. A story we were told where an overflowing toilet caused all inhabitants to sleep in the yard, not being fixed for weeks is not an uncommon story. There is promise though, $10 million dollars has been allocated to Mutitjulu as an NT Remote Aboriginal Investment towards replacing and refurbishing homes with a requirement for locals to be employed and the workforce at least 35% Indigenous. Costing has been formulated and when a typical house costs $750K, you really don’t get much for $10mil. Check out this graph on the trajectory of costing of remote indigenous housing[ix], it’s obscene! *Gasp!

When enquiring about a designer for the new work they replied with, ‘it doesn’t matter as long as WE are a part of the consultation’. Gary praised the process of Greg Burgess and his team who set up an office in Mutitjulu to work with the community.

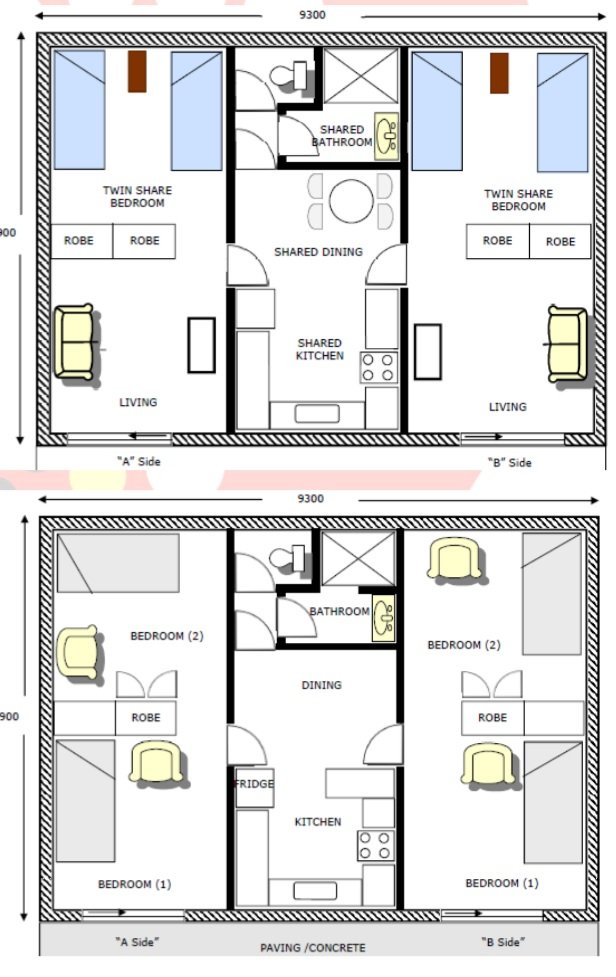

On the other side (Yulara side) the hotels are being revamped and the most interesting part of it all is the staff accommodation. For the more short term workers in hospitality etc. they are housed in what is known as “Share Share”. As one would in boarding school, two adults share a room with no walls for privacy and only one end where a sliding entrance door is receiving natural light & air, walking through someone’s ‘bedroom’ to get to your own. A lady we spoke with when she first arrived shared a bedroom with her manager, surely not great way to escape work hour woes.

Exhibition, Thursday 9th, august

Places often become important as people develop, through extended inhabitation, memories and meanings. This is often the way we try and understand a place, by talking with locals and hitchhiking deep into their history and knowledge. Uluru’s incredible power to exert an instant importance, is perhaps, why Yulara does not seem to have a depth to its inhabitation. The celebration of the rock as an isolated attraction reduces the slow revealing that extended inhabitation offers.

This tourist whitewash that pervades many aspects of Uluru also creeped into our exhibition and thinking. Proposing alternate visions of the future at the pivotal year of 2084 (The end date of the 99 year lease) on a series of post-cards. A subversion of the most tangible, mass produced tourist paraphernalia, these hand-made, limited edition, considered and hand-drawn cards aimed to provoke thought about inhabitation in the otherwise semi-inhabited tourist haven.

The pack of post cards. Offend and baffle your relatives! Nine visions of Uluru in the year 2084!

A small description on the back of each post-card gives one food for thought. The order is the text matches the same order as above.

Suggestions

- Sun is a killer, consider where timber is used

- Work with local groups to give ownership and pride to places and spaces

- A central courtyard with a variety of 'free' spaces to sit, watch and stay is an excellent option especially in a transient town like Yulara.

Inbetween (Uluru to Warburton)

Sunday 27th August – 6th September 7, 2017

Westwards, the first day took us past Kata Tjuta at sunset. The red conglomerate was amplified in space by the last rays of unadulterated desert sun. Breathtaking and silent, until the sun fades and the convoys of AAT Kings tour buses pass in return, racing back to the resort, strict schedule.

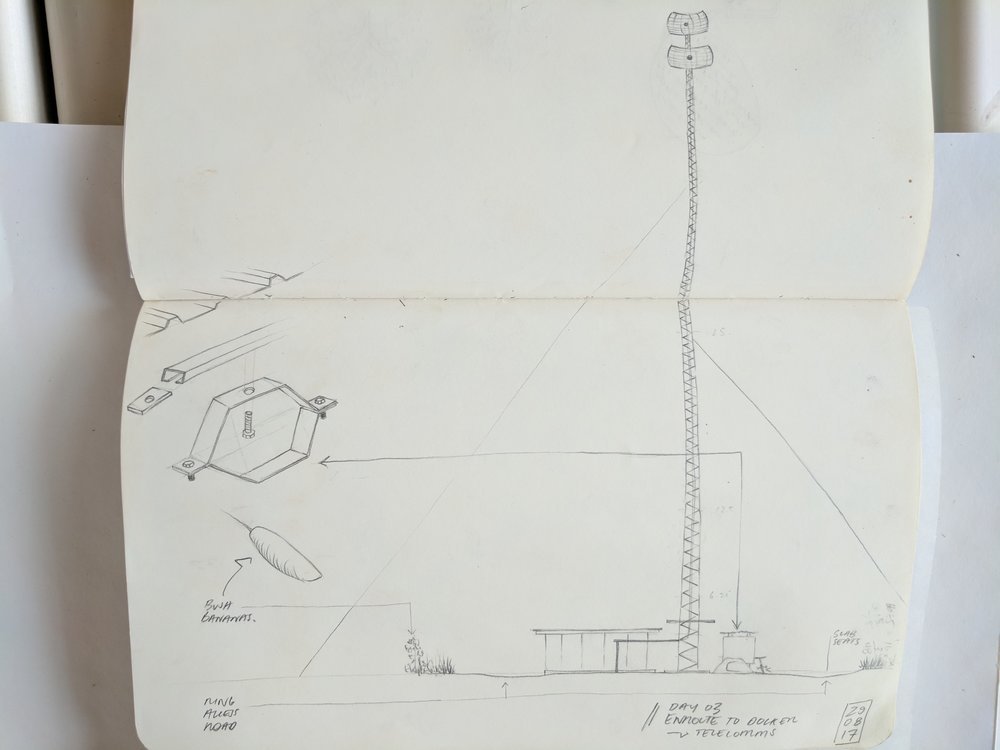

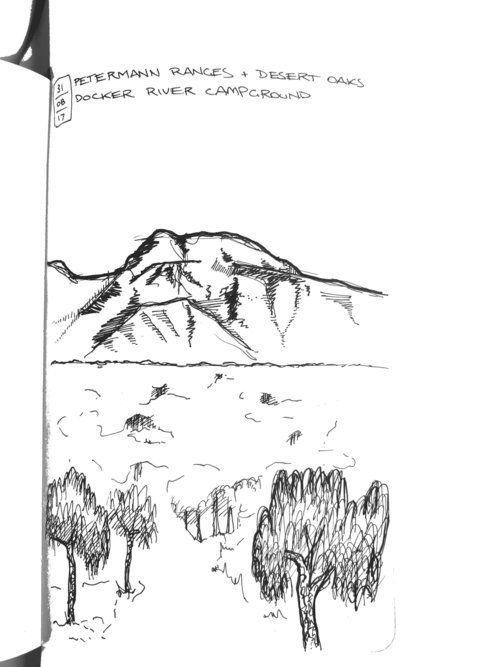

Undulating sand hills, quite similar to the landscape approaching Uluru, overplayed with oatmeal coloured tussocks, spinifex spikes and lethargic Desert Oaks contrast against sunburnt red sand. Corrugated and sandy roads along with a Bore water refill saw challenging and sandy days and salty morning teas into Docker River and the WA border. Anticipating to be Stop 15, things just didn’t work out as planned (it’s the way ‘time’ works out here) and so we continued westwards to the border. Just before Docker the Petermann Ranges made a reappearance and continued. Flanking us either side of the road for many km’s, the deep red rock outcrops and formations were glorious. The scale almost unfathomable. We witnessed some really interesting abandoned indigenous housing at Puta Puta and Lasseter’s Cave which seems to be an attempt at something different than what we’ve seen. Although, abandoned.

The arid landscape changed constantly with lone standing clumps of grass trees, ghost gums, desert oaks and Mallee shrubs responding directly to microclimates and soil variations.

The Warakurna road house saw us having a day off to take a break. Home to the Giles Weather station, an important weather and climate observatory for the country, we witnessed the over-whelming morning release of the weather balloon before we hit the road in the grueling, chilly wind, prevailing SE morning winds, in the afternoon trending to change to a SW headwind. The landscapes approaching Warburton again changed with the disappearance of the Petermann Ranges, long, slow inclines, changing vegetation away from spinifex with burnt roadside country. Food was basic over the last stretch and rationed as roadhouse supplies dictated, essentially surviving on an oversupply of apples to make up for the lack of any other fresh food.

According to the local Anangu people at current it is Piriya Piriya season. Seasons are fluid and ‘named’ by reference to predictable weather conditions at that time of year, not just how we generally classify the next 3 months being ‘spring’. Now, it is the time when animals are breeding, food plants are flowering and fruiting and reptiles are appearing from hibernation. This leg has been distinctly different in reference to these things, we’ve found bush tucker plants flower including the delicious honey grevillea, last season’s bush bananas and quite a few snakes (large Mulgas and Western and Ringed Browns) and a range of lizards we’ve had to swerve around.

*Edited by the absolutely fantastic Jen Richards who has been working behind the scenes supplying us with research as we’re peddling along.

Cheers,

Dusty and Thirsty

[i] Sandstone with a high level of feldspar, creating granite like surface flaking.

[ii] An event that leads to a large structural deformation of the earth’s crust and uppermost mantle due to tectonic interaction.

[iii] Welcome to Anangu land: World Heritage at Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, ro.uow.edu.au

[iv] www.sbs.com.au/nitv/nitv-news/article/2017/06/21/mutitjulu-community-was-ground-zero-nt-intervention-ten-years

[v] Manta tourism guide, Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia Pty Ltd 2017

[vi] Camp dogs or “cheeky dogs” are far from the kinds of domestic dogs we’re used to. Something too when you first experience is hard to swallow. These are the terms describing the mongrel dogs hanging around communities. Often they are hungry, treated in a different manner, diseased, injured, un-nooded (hence the amount) and at times aggressive. Rocks in hand are the solution when they come running for the bike, viciously barking trying to bite shoes and tyres.

[vii] Manta tourism guide, Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia Pty Ltd 2017

[viii] http://www.coxarchitecture.com.au/project/ayers-rock-yulara/resort/

[ix] https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5450868fe4b09b217330bb42/t/54756128e4b0f1adacec2ac4/1416978728332/Cost-of-remote-housing-construction-industry-views.pdf